Turkey loves its cheeses. Along with bread, it seems that no sofra (table) is complete without it in some form or another. At the breakfast table, cheese is usually served (in all its glory) by itself. Rarely will two cheeses be served on the same plate. If you are looking for the classic post-dinner cheese plate, go to France. There are other dishes, at breakfast, showcasing the love of cheese, but on a more subtle level. Dishes like börek (flaky layered phyllo) and gözleme (savoury crepe with various fillings) feature cheese, but it is not the star. Whether you can see it or not, cheese is somewhere on the table.

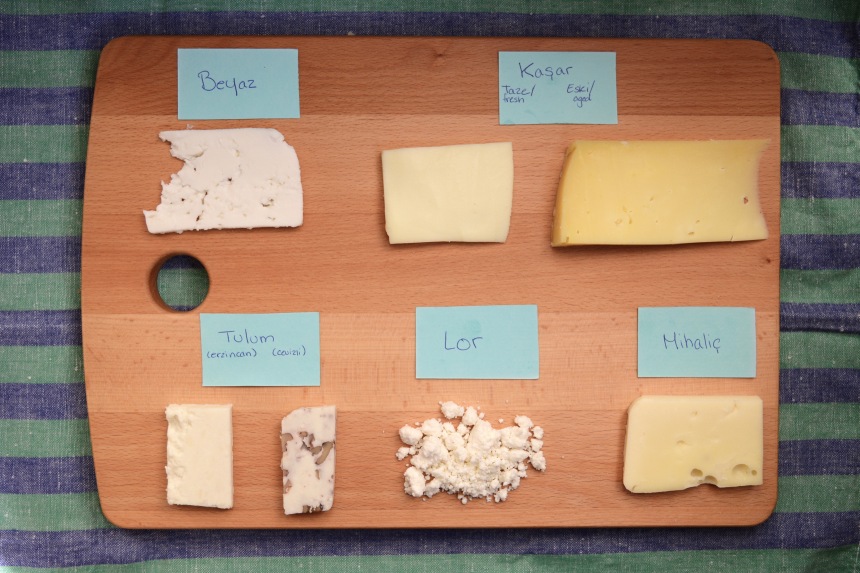

The best part of Turkish cheeses is also its detriment. Traditionally, the dairy product is produced differently in each region. Producers made do with what nature gave them: terrain, climate, animals, and so on. These procedures eventually turned into tradition. So that today, you can find the same type of cheese in every region and each one tasting different from the last. While variety is great, it also means that we’ve only tasted a fraction of what is out there. We’ll just have to keep on tasting. Damn. Below we’ve charted the five most popular and tradition Turkish cheeses: beyaz, kaşar, tulum, lor, and mihaliç.

From humble tables to the most elaborate to the grimiest of çilingir sofrası (rakı table), cheese does not discriminate – it makes its way onto every table.

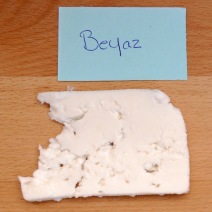

Beyaz

More often than not, Turkey’s beyaz cheese is compared to the Greek Feta. Don’t ever call it that, though.* True to its name, this cheese is white (beyaz means white) and it can be made from just about anything that produces milk. It is a fresh cheese that has no skin or rind. Fresh milk is curdled from rennet, which is then strained, moulded, and left to mature in brine for at least three months. The white cheeses that are higher in fat are generally smoother – better for spreading on toast. Those with a lower fat content are firmer and better for crumbling over a salad or, say, served a slice of kavun (melon) and a glass of rakı.

While it may seem like a white cheese is a white cheese is a white cheese, there are a surprising amount of varieties. And, it’s true; you can taste (and sometimes see) the difference. This difference depends on several factors such as the breed of animal and its diet as well as the environment, region, and season the cheese was produced. Because the cheese is a standard, you’ll find it in every corner of the country. And, naturally, each corner has its own way of making it.

While it may seem like a white cheese is a white cheese is a white cheese, there are a surprising amount of varieties. And, it’s true; you can taste (and sometimes see) the difference. This difference depends on several factors such as the breed of animal and its diet as well as the environment, region, and season the cheese was produced. Because the cheese is a standard, you’ll find it in every corner of the country. And, naturally, each corner has its own way of making it.

You’ll find beyaz everywhere, from supermarket chains to corner stores. However, it has been our experience that the best beyaz peynir come from the cheese makers at the weekly neighbourhood market.

*Not only might people get upset, but also ever since receiving the right to hold a designation of origin, only white cheeses that are 100% sheep’s milk or up to 30% goat’s milk “may bear the name ‘feta.’”[1]

Kaşar

Kaşar is probably most at home in Turkey’s Thracian region. When it’s not served by itself at breakfast, you’ll usually see it in tost (a kind of grilled cheese sandwich). Kaşar is made from boiling the milk curds in salt water. Not only does this step flavour the cheese slightly, but it also softens the cheese to a dough-like consistency, which helps it fit into any mould. At this point, a cheese maker will usually divide the cheese in half; one part is ready for consumption, the other half will be reserved for ageing. The fresh cheese is known as taze kaşar or fresh kaşar. It’s a soft tasting cheese that has often been compared to mozzarella (albeit not as soft and creamy). The other cheese, known as eski or old kaşar, will be formed into wheels, stacked and preserved for aging. During the process, the wheel forms a hard edge and a deeper colour. This aged version makes for a much stronger cheese – it has a bite.

Tulum

Tulum is traditionally made from goat’s milk. The cheese curds are strained and the crumbly leftovers are conventionally packed into goatskin (which might explain its name, tulum means coveralls – or, more casually, a onesie) and left to mature for at least three to six months. The cheese is produced throughout the Black Sea and along the Aegean coasts and each region makes its own kind. In many cheese shops and delis you’ll find Izmir tulumu right next to Erzincan tulumu. The primary difference being that the tulum made along the Aegean is kept in salt water, making for a stronger consistency and richer flavour. Some varieties of tulum are not necessarily regional but simply brilliant. If ever you come across a cevizli tulum (with walnut), we highly recommend picking one up. Tulum, no matter where it is from, often makes an appearance at breakfast – works great with toast and jam – but always works well with a glass of rakı.

Tulum is traditionally made from goat’s milk. The cheese curds are strained and the crumbly leftovers are conventionally packed into goatskin (which might explain its name, tulum means coveralls – or, more casually, a onesie) and left to mature for at least three to six months. The cheese is produced throughout the Black Sea and along the Aegean coasts and each region makes its own kind. In many cheese shops and delis you’ll find Izmir tulumu right next to Erzincan tulumu. The primary difference being that the tulum made along the Aegean is kept in salt water, making for a stronger consistency and richer flavour. Some varieties of tulum are not necessarily regional but simply brilliant. If ever you come across a cevizli tulum (with walnut), we highly recommend picking one up. Tulum, no matter where it is from, often makes an appearance at breakfast – works great with toast and jam – but always works well with a glass of rakı.

Lor

Lor is an especially interesting cheese because it is not made from strained milk curds like

the above. Rather, it is made from the leftover that’s strained out of milk curds. It is the

whey cheese of Anatolia — every great civilization created one. The end result is a dry crumble cheese whose consistency does not change too much when heated. Lor is rarely eaten on its own, but its subtle flavour is refreshing in börek and gözleme. Many (including everyone’s favourite, Wikipedia) compare lor to ricotta cheese. Be warned. If you are living in Istanbul and a recipe calls for ricotta, avoid the pre-packed stuff. Those are often intended for traditional Turkish dishes like börek. On the other hand, don’t let us stop you from playing with your food!

Mihalıç (or Kelle)

One of the older cheeses produced in Anatolia, stories tell us that during the Roman period, a small migrant village along the coast of the Marmara Sea had a way of making

their milk last throughout the year. They emptied their vessels of milk and boiled it. They strained the curds with cloths that they hung anywhere they could. The hanging cheeses were so abundant that the site inspired the Romans who later passed on the cheese making methods throughout Europe. While it is easy to poke hole in stories and legends, on aspect remains certain about this story. Cheese, along with so many preserves, was made so that travellers could easily transport their food and eat it, too.

their milk last throughout the year. They emptied their vessels of milk and boiled it. They strained the curds with cloths that they hung anywhere they could. The hanging cheeses were so abundant that the site inspired the Romans who later passed on the cheese making methods throughout Europe. While it is easy to poke hole in stories and legends, on aspect remains certain about this story. Cheese, along with so many preserves, was made so that travellers could easily transport their food and eat it, too.

Similar in production to kaşar, mihalıç cheese curds are also strained and placed in warm water (40-45°) and left to harden. Like taze kaşar, mihalıç is slightly firm and elastic, but with little pores. Mihalıç is another popular breakfast cheese, but because of its saltier taste it’s also used to top baked dishes like pizza or güveç (vegetables or shrimp cooked in a clay pot in the oven).

[1] The Oxford Companion to Cheese. Edited by Catherine Donnelly. NY: Oxford University Press (2016): 270.

I should thank you for you, for your beautiful sharing in this blog. I live in Istanbul but everyday I learn and fine something new. Especially in your blogs too. I wanted to say this. We love cheese, white and kaşar, and not easy to find the best one in this city. In the old days , it wasn’t like that, you can find in our local grocer too. The point in here, to find the healthy one, good one and of course tasty one… I follow your blog and your posts, I take note, I feel myself like a tourist and learning my city again 🙂 Thank you so much, with my love, nia

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh wow! Thank you for such delightful words! We love following your blog, too. Everything you post captures a whole new perspective on life.

Also, if you liked this post there will be more guides coming soon! Thank you again for your kinds words and thank you for following us, it is very encouraging!

LikeLiked by 1 person

How nice of you. You are welcome. I am so glad to hear that you follow my blog too. I will be waiting for your new posts… You are doing great work with all these posts. Thank you again, have a wonderful Istanbul days, Love, nia

LikeLiked by 1 person

And, there’s so much more too!

LikeLike